Columbia University, for example, has created an edX MicroMasters program, as they are known, focused on AI that will explore one of the most fascinating and fastest growing areas of computer science to date.

There’s a gaping skills gap in similar, white-hot areas such as big data analytics. Such is demand that traditional campus universities have been unable to supply enough talent to fill the void. This has opened up a “sweet spot” for online learning platforms, as edX CEO Anant Agarwal, calls it.

“We are in these huge in-demand fields, while most universities do not have programs in data science or AI,” he told BusinessBecause.

While most of the demand is for engineering talent, there’s increasingly a need for managers to understand how technologies like deep learning and AI, which are rapidly reshaping businesses across industries, will create opportunities and spur disruption.

“Artificial intelligence, deep learning, and the overarching analytics field are going to significantly change all facets of business,” says Shawn Mankad, assistant professor of information management at Cornell’s Johnson School of Management. “Knowing data science is an absolutely critical requirement.”

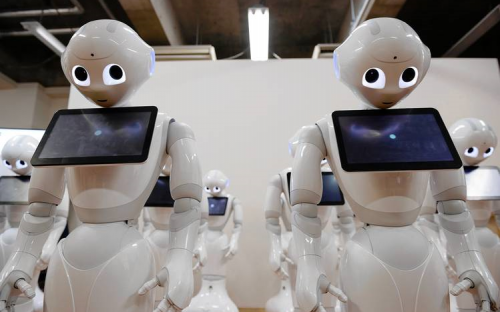

Because such fields are still relatively nascent, there’s a growing need for continuous education, as dramatic advances in areas such as AI and robotics continue to be made.

“The days when we could learn from 18 to 22 and have a productive and prosperous lifestyle are gone. This is the age of continuous learning,” says edX’s Anant.

This explains why edX’s courses are backed by leading global corporations such as General Electric, which has placed a $1 billion bet on big data and the Internet of Things, and which has endorsed Columbia’s AI program.

The shift highlights the increasing professionalization of edtech, as platforms focus on courses that can advance students’ careers. It’s a big departure from the age of Moocs, free online courses with high drop-out rates, which were initially met with scepticism by employers, says Patrick Mullane, executive director of Harvard Business School’s online learning initiative, HBX.

But companies are increasingly warming to digital credentials. Part of the appeal, according to edX’s Anant, is that they are flexible — courses like MicroMasters can generally be completed on the side of full-time employment.

“Employers just aren’t able to send their employees to spend one or two years getting a masters on campus. It’s unthinkable,” he says, adding that it also helps that firms recognize the brand appeal of institutions like MIT, which is one of 14 top universities that have created the MicroMasters courses.

This flexibility is attractive not just for large multinational corporations but for students too, who are increasingly questioning the tuition, time and also opportunity cost of getting a traditional university degree.

EdX’s MicroMasters can be completed in three to six months and are but a fraction of the cost of a degree at an Ivy League US school. A top MBA program, for example, can cost well over $100,000 a year.

The flexibility extends beyond the online realm. Like many of its competitors, edX lets MicroMasters students complete residential modules. It’s partnered with Pearson, one of the world’s top learning companies, to let students use its learning centres to meet peers and get in-person support.

This blending of bricks and clicks, which Anant calls “unbundling”, is increasingly apparent in higher education.

Now, MicroMasters can count toward credit and lead to an on-campus masters program. This is another big trend in online learning, which Ivan Bofarull, director of the Global Intelligence Office at ESADE Business School, expects to continue to spread. “This is only the beginning of a learning curve that is set to accelerate,” he says.

Sanjay Sarma, vice president for open learning at MIT, says: “MicroMasters broaden our admissions pool, and also allow learners to demonstrate their abilities.”

Such partnerships run counter to the narrative that traditional universities and business schools will eventually be disrupted by edtech players. Anant says: “Universities will not go away.”

But he adds: “Our education system needs to become nimble and flexible in order to keep pace with the demands of the corporate world.”

RECAPTHA :

bc

55

72

a9