You increasingly hear tales of ‘girlbosses' redefining success, ‘mompreneurs’ juggling their kids and their careers, and ‘SHE-eos’ breaking the glass ceiling.

And though there’s no denying that we’ve seen a steady increase of women holding senior positions in the workplace, these prettily packaged (and troublingly patronizing) terms hide the deeper, ongoing issues.

Though it’s true that a select few have managed to pierce through the glass ceiling, who do we actually refer to when we talk about successful ‘women in business’? And what are the limitations that women in the workforce consistently face?

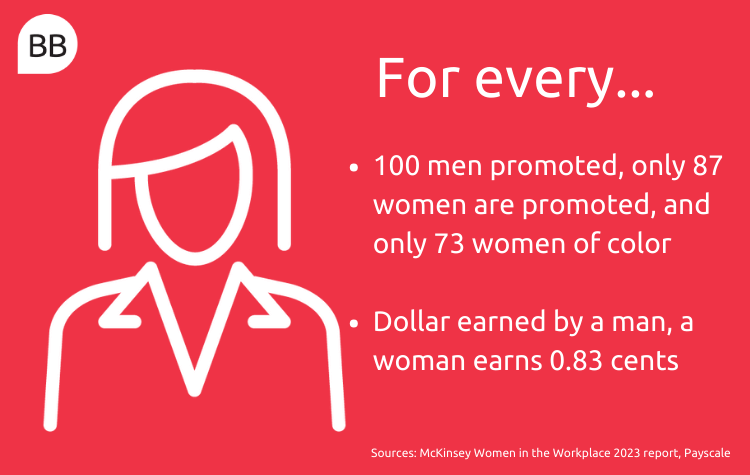

The gender pay gap still exists

Although considerable advancements have been made in the past few decades, men are still earning more than women. According to a recent Payscale report, a woman only earns 83 cents for every dollar earned by a man. CEO of Forté Foundation, Elissa Sangster (pictured below), puts this down to a lack of female promotion.

“In their early careers, women aim to surpass men and strive for leadership roles like directors and VPs,” she says. “But they’re not getting promoted at the same pace.”

The 2023 McKinsey Women in the Workplace report uncovered that for every 100 men promoted to managerial level, only 87 women are promoted, and only 73 women of color.

“This is a problem that starts at the first promotion level; we call this phenomenon ‘the broken rung’,” says Tijana Trkulja, engagement manager and co-author of McKinsey’s report. “Women struggle to take that first step on the corporate ladder, which is broken because more men are getting promoted.”

The reasons behind this are threefold. First, women still shoulder the majority of unpaid work. Dubbed ‘the extra shift’, women work full-time jobs and tackle more on the home front alongside their careers.

“Women are doing much more extra work, whether that’s caring for children, their elderly relatives, their partners, or the housework,” says Kate Sang, professor of Gender and Employment Studies at Edinburgh Business School, Heriot Watt University.

With their time and energy being stretched thinner, women burn out faster than men. McKinsey reveals that 43% of female leaders are burned out, compared to 31% of men at the same level.

“If you look at the gender pay gap by age, it really balloons at 35,” says Julia Bear (pictured left), associate professor of management in the College of Business at Stony Brook University. “This is when people are more likely to have family responsibilities; women are more likely than men to reduce their hours or work part-time.”

An OECD Paper reveals sticky floors as the second reason holding women back from senior positions. Sticky floors, defined as issues surrounding social norms, stereotyping, and gender discrimination in the workplace, account for 40% of the gender wage gap.

Kate explains how women frequently encounter both conscious and unconscious gender discrimination from their employers. She highlights how employers are less likely to choose women on the perception that their caring responsibilities will make them more likely to work less, or be less committed to their careers.

Sreedhari Desai (pictured), professor of organizational behaviour at UNC Kenan-Flagler seconds this. She emphasizes that the limitations women face surrounding pregnancy represent a hugely sexist institutional barrier.

“If a woman in business indicates starting a family, she will find she is not being assigned to prestigious projects anymore or take on initiatives that involve travel. Then, once a woman becomes a mother, she will be treated differently and as less capable,” Sreedhari says.

Corporate policies are also intrinsically unfavoring of pregnancy and the re-entry of pregnant women into the workforce. In the US, maternity leave is just 12 weeks. In addition to this, companies rarely have facilities for new mothers such as daycare assistance or lactation rooms.

Another consistent bias that women face is that they fare worse than men when it comes to discussing promotions and salary expectations.

“It’s not that women don’t negotiate hard enough, it’s that women receive more negative reactions than men when they do,” says Julia.

She asserts that women receive different offers than men to begin with. She explains that women are more likely to be offered lower salaries and benefits that are not necessarily career-enhancing.

A non-inclusive workplace environment is the third reason for gender inequality in the workplace. When an organization’s culture expects women to work 60-70 hours a week, they’re not factoring in the unpaid work that women tend to do alongside their jobs.

“This cut-throat environment is a very masculine culture that is really motivating for men and quite challenging for women,” says Julia. “For men, it’s a way for them to prove themselves and their masculinity. There could be a lot of talented women who just simply aren’t satisfied with that culture.”

As women are not wholly incorporated into the masculine workplace culture, they are less likely to put themselves forward for a promotion in the first place.

“Ingrained sexism is not talked about enough,” says Kate. “Masculine norms are so ingrained in organizations that women will self-select themselves out of promotions.”

Who’s actually making it to the C-suite?

©Vadim_Key

Kate reveals how although it may look like there are more women making it to the C-suite, the truth is that a small number of women in the workforce are sitting on increasingly more boards.

The McKinsey Women in the Workplace report emphasizes how women of color (WOC) only account for 6% of C-suite leaders.

“If you look at the demographic of female C-suite leaders, they’re largely privately educated, white women,” Kate explains. “There’s a lack of WOC on the board, and there’s also a lack of class difference.”

Women of color experience harsher, everyday workplace environments. This materializes when white employees interrupt and speak over them, question their judgement, and challenge their competence. It also shows up through disrespectful and othering behavior— tokenism, microaggression, and racial bias.

“This is especially true when these women are both the only women in their company and the only person of their race and ethnicity,” says Tijana (pictured). “They are what we call a ‘double only’, which means they’re two to three times more likely to experience othering behaviors than women overall.”

In the McKinsey report, women of color were more than five times more likely to be confused with someone else of the same race or nationality in the workplace.

Emma Bolger (pictured below), lecturer in Career Guidance and Development at University of the West of Scotland, emphasizes how businesses are failing to follow through with their diversity efforts.

“There’s more work that we can do to reflect what the workplace looks like,” she says. “A lot of the diversity marketing in companies is often a falsehood compared to what the environment actually looks like.”

To combat this, Tijana emphasizes the importance of allyship training in businesses. The McKinsey Women in the Workplace research demonstrates that although many white employees consider themselves allies to women of color, far fewer have anything to show for this, such as publicly acknowledging their ideas, providing mentorship and sponsorship programs, or advocating them for new opportunities.

What can businesses do to address these obstacles?

It’s clear that businesses whose culture falls short of inclusivity need to make changes to achieve gender equality in the workplace. One way that companies are trying to do so is by reducing unequal distribution of labor through extended paid paternity leave.

However, men aren’t seeming to take these benefits when they’re available. Although 80 out of 187 countries worldwide offer paid paternity leave, less than 50% of fathers actually use it.

To tackle this, Nordic countries are subverting gender norms by creating an expectation that men must take time off work. The ‘daddy quota’ enforces a use-it-or-lose-it parental leave exclusively for fathers, which led to nine of ten Swedish fathers to take leave.

“Organizations must really explicitly make parental types of leaves inclusive of fathers,” says Hannah Riley Bowles (pictured below), senior lecturer in Public Policy and Management at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Men are more likely to [take] leave if their senior manager or family member has done it. Social modeling is so critically important.”

Although paid paternity leave is an important factor to consider, Kate still emphasizes how unpaid care work doesn’t stop when a child reaches 18—women are still more likely to take care of elderly relatives.

She highlights the importance of company communication, not only through salary transparency (which is beneficial to both men and women), but also through providing transparent opportunities for promotion and changing the workplace to cater to more flexible working hours and remote settings.

“Managers have developed a set of soft and technical skills when working with flexible, remote teams,” Hannah agrees. “If we can leverage those new competencies coming out of the pandemic to find ways of increasing opportunities for promotable roles that involve flexibility and online work, I think there’s a huge opportunity.”

When it comes to improving diversity and inclusion (DEI) efforts, Tijana says that businesses should actively measure and track metrics around diversity, holding themselves accountable when their outcomes don’t meet their goals. These measurements should include hiring and promotion outcomes by both gender and by race and ethnicity, and the intersection of both, so that they can understand exactly where they should focus on improvement.

“We know that women of color who say they have strong allies are 84% more likely to be happy in their job, and 47% less likely to consider leaving their company,” Tijana says.

“When it comes to inclusion, we need to think about providing mentorship and sponsorship programs to WOC, supporting Employee Resource Groups, listening and acting on employee’s concerns, and ultimately making sure that employees feel supported and heard in these organizations.”

Although there’s been progress towards a more level playing field between men and women in the workplace, there are no quick fixes.

What is certain, however, is that if these efforts are not supported by clear legislative frameworks, then businesses are unlikely to follow through with their promises.

It shouldn’t be up to women to pull themselves off sticky floors, hurdle over broken rungs, and break through glass ceilings. Hiding inequality behind labels of ‘SHE-eo’, ‘mompreneur’ and ‘girlboss’ will only serve to create further sexism in the workplace. To see change, businesses need to put their words into action.

This article was originally written in October 2021 and updated in March 2024.

Next read: Why Is There A Problem With Gender Diversity In Tech?

BB Insights explores the latest research and trends from the business school classroom, drawing on the expertise of world-leading professors to inspire and inform current and future leaders