You can cycle to work on a Lime bike, you can get home in an Uber. You can order food from Deliveroo and you can get rid of your old food on Olio.

As resources have become more expensive, and our awareness of reducing our consumption has grown, digital platforms and startups have offered a solution—sharing.

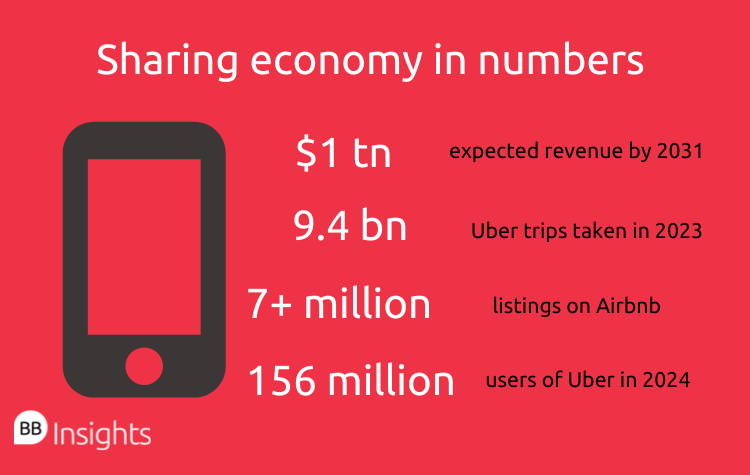

The sharing economy is expected to grow in excess of $1 trillion by 2031.

So what is the sharing economy? Where did it come from, and where is it going?

What is the sharing economy?

A sharing economy is defined as an economic system in which assets and services are shared between private individuals.

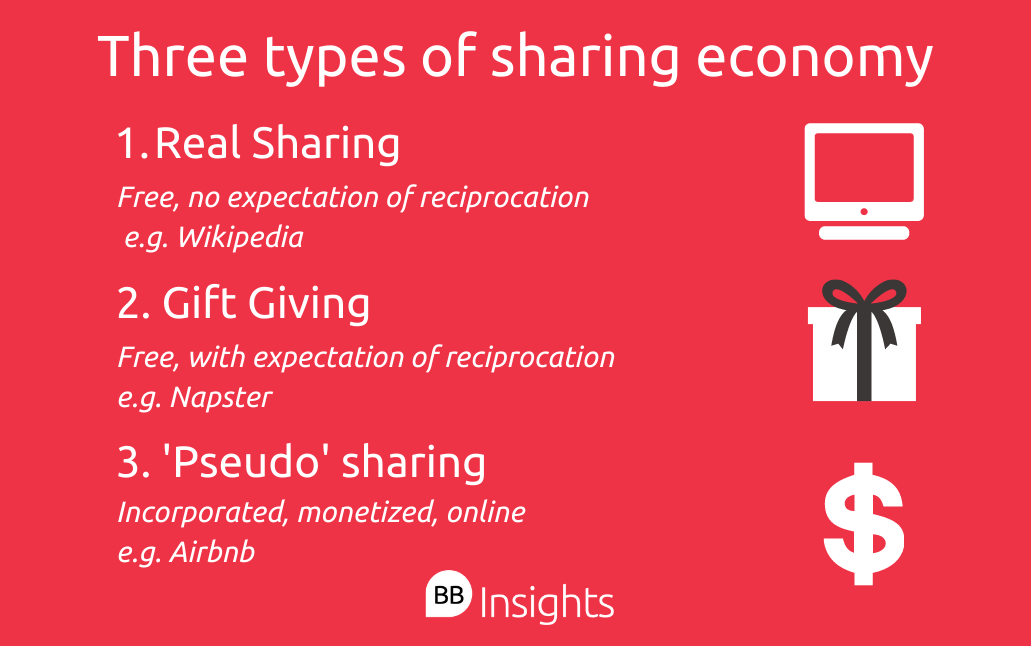

It’s used as an umbrella term for many different services, apps, and products. Attila Marton, professor of digitalization at Copenhagen Business School, believes these can be divided into three distinct concepts.

First, you have the real sharing economy. This is sharing in its simplest form, such as food between a family or household products between flatmates. Wikipedia, for instance, came about as a platform where users could voluntarily contribute and share knowledge.

Secondly, you have gift giving. You share a product or service—like a birthday cake—in the expectation that others will reciprocate in the future. This concept grew out of the early days of the internet and the open source movement, where programmers would make software and coding freely available.

Napster, the early online streaming service, allowed users to upload their own music, in return for accessing other people’s music.

Thirdly, we have the pseudo-sharing economy, which best encapsulates today’s sharing economy. This is an incorporation and monetization of the informal economy—small, unregulated transactions like street food, taxis, or anything that is seen as ‘off the books’.

In this sense, many believe the term ‘sharing economy’ to have been misappropriated.

“The two most prominent sharing platforms—Airbnb and Uber—are very commercial and have very little to do with actual sharing in the sense of solidarity and community,” insists Christoph Lutz, professor of communication and culture at BI Norwegian Business School.

Why has the sharing economy grown so quickly?

Technology has been the biggest driver behind the sharing economy’s growth.

“Through digitalization, corporations have been able to tap into the informal economy and capture some of its value,” Attila explains. Micro-transactions and peer-to-peer reviewing have facilitated ease and trust in online sharing.

“These apps have brought underutilized resources online and efficiently matched them to demand,” says Ming Hu, professor of operations management at Rotman School of Management at University of Toronto.

It also plays into a culture shift for millennials and Gen Z-ers.

“People, especially young people, are more comfortable with accessing goods than owning them,” Christoph explains.

Spotify and Netflix, although not strictly sharing platforms, encapsulate the same sense of accessing shared resources rather than owning physical copies. The same logic can apply to anything from belongings on BorroClub to a spare car seat on BlaBlaCar.

Big investment has undeniably played a part in the growth of sharing platforms. SoftBank invested big sums in Uber and WeWork while they were scaling and attempting to get market share. While these companies still grapple with profitability, and with gaining public ownership, they are as reliant on investment as ever.

Is the sharing economy sustainable?

Many sharing platforms pitch an alternative to waste, pollution, and excess. But a question mark has been raised over whether they do more damage than good.

Bike sharing apps promise to take cars off the roads and encourage exercise: but photos of bike graveyards, from Chinese bike-sharing app Ofo, show the harm of sharing gone wrong—in their case, fast expansion in an oversaturated market.

It's suggested that clothes sharing platforms may encourage people to buy more clothes than they ordinarily would in the knowledge that they can hire them out.

“There is an environmental downside that we try not to think about as consumers,” Ming adds.

Sharing platforms also pose a threat to local economies. Airbnb has been accused of contributing to rising rent and gentrification. In cities like Berlin, Airbnb has been used to avoid local rent caps, while simultaneously making people dependent on subletting out their rooms in order to make rent.

“It profits from growth, while risks and losses are externalized to its environment,” says Attila.

Financially, it’s still uncertain whether sharing platforms are able to successfully turn a profit—exemplified by the uncertainty around Uber and WeWork’s failed initial public offerings (IPO).

“The low number of profitable platforms and the speed with which new initiatives disappear suggests that financial sustainability is mostly not given,” Christoph argues.

Attila speculates that the business model of companies like Uber is self-defeating.

“What benefits the model is that the more Ubers there are on the road, the cheaper it will be for riders, and the shorter they’ll have to wait. But follow this to its natural conclusion, and it will create congestion, and you’ll have more empty Ubers driving around.”

What's next for the sharing economy?

There is a clear need for sharing economy platforms to change and diversify their revenue, towards more lucrative industries of the future—artificial intelligence and data.

Aurora, the self-driving car startup backed by Uber investment, has a valuation of over $10 billion following Uber's partial stake in the company. In 2024, Uber announced plans to bring Cruise autonomous driving vehicles to its platform.

Airbnb is also partnering with local tourism industries, now offering Airbnb Experiences.

Just as large existing platforms are updating their offerings, it’s likely that sharing will be applied to new, relevant industries. Construction, Attila believes, is one space where tools, resources, and workforces can be shared.

Energy also seems to present a sharing opportunity. Community microgrids enable small-scale access to renewable energy, sharing the cost between users and selling excess to regional or national grids.

This small-scale sharing is gathering traction through sharing platform cooperatives. These are putting more emphasis on ownership, for both workers and users. UK-based ride-sharing app Ola, for instance, takes 15% commission from its drivers (compared to the approximate 25% cut that Uber takes from every fare).

“Time will tell if these present a viable alternative to large sharing platforms,” Christoph says, “But it’s an interesting counter-trend where we’ll likely see much more movement in coming years.”