As part of the three-day executive education program at Ashridge Business School, researchers monitored changes in the managers’ heart rates to analyse the body’s response to stress, and their performance under pressure.

When a stressful situation is perceived as a challenge, the brain and body become moderately aroused, optimising decision-making. But if a situation is perceived as a threat, we become over-aroused and prepare for retreat, reducing cognitive functioning.

“You won’t learn the most important elements of being a leader by reading a book or sitting static in a classroom. The real challenges of leadership are practical, not theoretical,” says Megan Reitz, director of and co-researcher on the school's program.

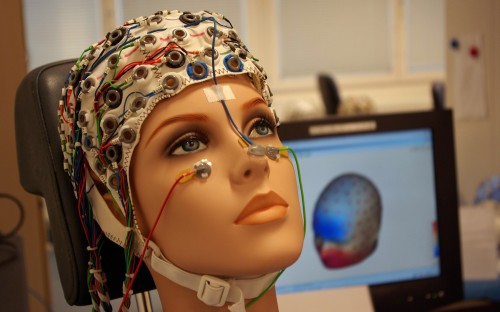

The leadership course at Ashridge is one of a growing band of business school programs that bring medical equipment and behavioural techniques from laboratories into the classroom. Heart rate monitors and brain scanning machines are being used to give executives an edge in the most stressful parts of their jobs, and to improve decision making.

Business schools are finding a way into the hearts and minds of managers. Medical devices and neuroscience are being deployed on MBA students, which helps prepare them for careers in marketing, product development and even consulting and finance, say management professors.

The program at UK-based Ashridge was developed on the back of research into what top executives find most stressful. Researchers found that emotions like fear, anxiety, stress and anger narrow our focus and inhibit our concentration, and ability to co-ordinate well with others and take in new information.

In the US, researchers at MIT Sloan’s Neuroeconomics Laboratory are exploring brain-scanning technology to measure brain activity in experimental subjects who are making real decisions.

While fMRI scanning is an expensive technology, it can provide valuable marketing insights. “People may believe that they drink Coke for the taste, but in reality they may be responding mainly to the brand image,” says Drazen Prelec, professor of management science and economics at MIT: Sloan.

He teaches one neuroscience session within his class, and says that it is an advantage for MBA students to understand human nature – which can influence careers, particularly in marketing and product development.

“Neuroscience will change social science and our understanding of the human being, and therefore it will change management,” adds Drazen.

The use of brain-scanning techniques has been used for several years in the US. At Emory's Goizueta school, professors used MRI techniques with EMBA students to see who made ethical decisions.

One of the more extreme medical techniques involves magnetic resonance imaging machines, which use magnetic fields to form images of the brain. Such hospital practices are used at Bocconi University in Italy, to discover why some managers are more innovative than others.

But most medical practices adopted for business education involve behavioural science. Warwick Business School in the UK runs a Mooc based on the subject, which filled up within 48 hours of launching. More than 20,000 people have enrolled so far.

There are two powerful advantages MBA students can gain from behavioural science, says Professor Nick Chater, who is head of the Behavioural Science Group at Warwick. It can improve our ability to make decisions, to understand better how other consumers, colleagues and entire organisations make decisions; and can help students learn to think in terms of experiments.

“Applying a rigorous experimental approach to testing out different marketing strategies… May have a similarly revolutionary effect on the business and policy world as the application of randomised controlled trials has had in medicine,” Nick says.

The practice is a key element of the school’s MBA, while its other master’s programs have modules on behavioural science. Students study core subjects like finance and strategy, alongside areas such as human decision-making.

The importance of emotion in decision making is particularly important on the trading floor. Researchers at MIT: Sloan have analysed data gathered by wiring up traders at the Boston Stock Exchange.

Warwick runs a similar course. “We have a behavioural finance module where we look at the psychology going on in investment decisions and in stock market behaviour,” says Nick.

Neuroscience has proved so popular that Germany’s Frankfurt School of Finance and Management launched an open enrolment program called “Neuroleadership”.

The program uses medical tests to analyse physical and mental stress levels. If executives show a persistently high level of stress, they are in “survival mode”. “In this state, they are not able to solve problems creatively – they just focus on survival, meaning they either act offensively or defensively,” says Sonja Thiemann, head of leadership and strategy at Frankfurt.

The theme of the course centres on the idea that executives can be more open-minded, creative and innovative – establishing a culture of growth within teams and companies.

“Looking into neuroscience [will] help post-graduate students to develop their own style in leading themselves and others,” Sonja says. She adds that Frankfurt’s corporate clients are keen to use these new insights in their leadership and change management programs.

But do employers value MBAs who have developed these techniques?

Nick from Warwick thinks so. He points out that private sector organizations have been setting up behavioural insight teams. “Increasingly, and more importantly, a background in behavioural science is a critical component of a broad business background,” he says.

Lee Waller, director of the Ashridge Centre for Research in Executive Development, says that by revealing the science behind making learning memorable, it helps professionals transfer that learning into the workplace.

Drazen from MIT thinks that neuroeconomics techniques are helpful for students, even in consulting and finance careers. “If you are a company that’s engaged with a science but you have no internal expertise, that puts you in a very uncomfortable positon,” he adds.

Megan from Ashridge thinks that during uncertain economic times, people who can manage their emotions and anxieties are needed. She says: “Traditional lectures and seminars just don’t cut it anymore. Students need true to life business challenges, and the opportunity to act out different behaviours.”

RECAPTHA :

cf

3f

27

62